TL;DR

Autonomous/agentic systems need safety layers that can flag abnormal behavior early, even when we don’t have perfect labels for attacks. In this project, I built an anomaly detector over system-event logs and learned a key lesson that transfers directly to agentic AI in retail investing:

-

A detector calibrated for trust (low false positives) in normal operations can fail under incident conditions where the base rate shifts.

-

The fix isn’t “a better model” alone — it’s resilience-aware alerting policy (adaptive alert-rate / incident mode).

-

Parsing structured arguments (

args) boosts detection of high-severity behavior, but can increase noise in ops-like settings without proper calibration. -

Error analysis showed false positives cluster in a small set of benign system services (e.g.,

systemd-*, management agents), motivating policy layers (allowlists) and context-aware baselines.

What you’ll get by the end

By the end of this post you’ll have a template for building a practical safety layer:

-

A reproducible pipeline for anomaly detection on event logs

-

Two operating modes:

-

Trust mode: conservative alerting for day-to-day operations

-

Incident mode: adaptive alerting to maintain recall under attack-heavy conditions

-

-

A concrete methodology for evaluating:

-

ranking quality (PR-AUC/ROC-AUC)

-

operational performance (precision/recall at a chosen alert budget)

-

severity behavior (does the detector rank “evil” events higher without seeing them in training?)

-

-

A clear mapping of these ideas to agentic AI for retail investing (tool calls, order placement, account actions)

Problem + why the data forces a “trust vs resilience” design

In security monitoring, the hardest part isn’t building a model — it’s deploying something people can trust. If a detector fires constantly during normal operations, analysts and users stop listening. But if you tune it to be quiet, it can fail when the environment shifts into an incident.

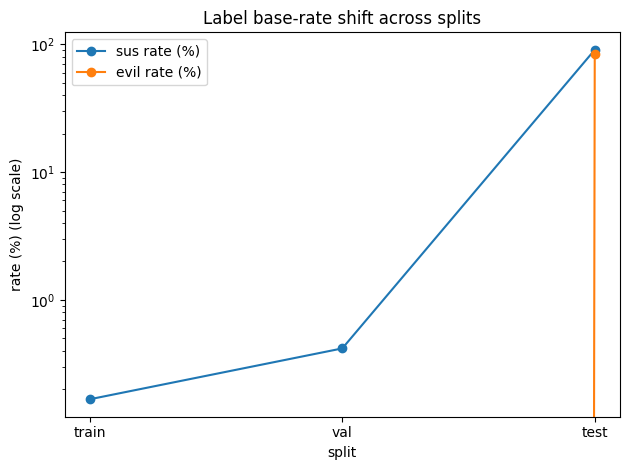

This dataset makes that tension visible. In the training and validation splits, suspicious events (sus=1) are rare (≈0.17% in train and ≈0.4% in validation), and there are no evil=1 examples at all. In contrast, the test split is attack-heavy: most events are suspicious and a large portion are labeled evil=1. That means a classic supervised “evil detector” can’t be trained from train/val — the realistic approach is one-class / unsupervised anomaly detection trained on mostly normal behavior, with an operational policy that adapts when the base rate shifts.

This is exactly the pattern we’ll see in agentic systems (including agentic retail investing):

-

Trust mode (normal): keep alerts low and interpretable.

-

Incident mode (elevated risk): increase monitoring budget and adapt alert thresholds/rates to maintain recall.

Dataset overview

The dataset consists of system event records captured from hosts over time. Each row describes a single event (e.g., close, socket, clone) along with the process/user context and a structured argument list. This structure is similar to what an agentic system produces when it interacts with tools: each tool call has a timestamp, an identity, an action type, and parameters.

Key columns

-

timestamp: when the event occurred (relative time)

-

processId / threadId / parentProcessId: process lineage

-

userId: user context (useful for separating system vs user activity)

-

mountNamespace: namespace context (useful in containerized environments)

-

processName / hostName: human-readable process identity and host

-

eventId / eventName: event type

-

returnValue: outcome signal (e.g., error/non-error)

-

argsNum: number of arguments associated with the event

-

args: a structured list of arguments (stored as a string representation of a list of dicts)

-

sus: label indicating suspicious activity (broad anomaly)

-

evil: label indicating malicious activity (high severity)

Label behavior across splits (important)

A key property of this dataset is that evil=1 is absent from training and validation, but present heavily in the test split. That means we cannot train a supervised “evil classifier” using the provided training data. Instead, we treat this as a realistic security setting: train on mostly normal data, tune on rare suspicious events, and then check whether the anomaly score generalizes to high-severity behavior.

Figure 1 — The dataset exhibits strong base-rate shift: validation contains rare anomalies and no evil events, while test is attack-heavy. This motivates one-class anomaly detection plus adaptive alerting policies (trust mode vs incident mode).

import pandas as pd

import ast

# Load splits (already loaded earlier in our notebook as dfs)

train_df = dfs["train"]

val_df = dfs["val"]

test_df = dfs["test"]

print("Columns:", list(train_df.columns))

print("\nTrain head (selected columns):")

display(train_df[["timestamp","processName","eventName","hostName","argsNum","returnValue","sus","evil"]].head(5))

def parse_args_cell(s):

"""

args is stored as a string that looks like a Python list of dicts.

We parse it safely using ast.literal_eval.

"""

if pd.isna(s):

return []

s = str(s).strip()

if s == "" or s == "[]":

return []

try:

v = ast.literal_eval(s)

return v if isinstance(v, list) else []

except Exception:

return []

print("\nParsed args examples:")

for i in range(3):

raw = train_df["args"].iloc[i]

parsed = parse_args_cell(raw)

print(f"\nRow {i} raw args:", str(raw)[:120], "...")

print("Row", i, "parsed args:", parsed)

What the args field looks like

The most information-dense column is args, which stores event parameters as a list of objects with fields like:

-

name(e.g.,fd,option,flags) -

type(e.g.,int,unsigned long) -

value(string or numeric)

Here are real examples from the dataset after parsing:

Example A — multi-argument event with a high-signal token

[

{'name': 'option', 'type': 'int', 'value': 'PR_SET_NAME'},

{'name': 'arg2', 'type': 'unsigned long', 'value': 94819493392601},

{'name': 'arg3', 'type': 'unsigned long', 'value': 94819493392601},

{'name': 'arg4', 'type': 'unsigned long', 'value': 140662171848350},

{'name': 'arg5', 'type': 'unsigned long', 'value': 140662156379904}

]

[{'name': 'fd', 'type': 'int', 'value': 19}]

Threat model: what “anomalous” means in these logs (final)

4. Threat model: what are we trying to detect?

This project treats anomaly detection as a safety layer over system activity. The goal is not to classify every possible attack type, but to surface events that deviate from normal behavior in ways that warrant investigation.

In this dataset, most activity is file and process related. The top event types in training include:

-

close(218,080),openat(209,730),security_file_open(148,611) -

fstat(80,071),stat(41,931),access(14,383) -

plus smaller counts of

socket, directory listing (getdents64), and capability checks (cap_capable)

These are exactly the kinds of “everyday” system calls that dominate normal operations—meaning an effective safety layer must detect anomalies within a sea of routine behavior.

On the process side, training is dominated by a few processes, especially:

-

ps(406,313) andsystemd-udevd(189,292) -

sshd(91,762) -

plus

systemd-*services and agents likeamazon-ssm-agen

This matters because anomaly detectors often end up learning “common service behavior,” and will tend to flag rare process behaviors as suspicious—sometimes correctly, sometimes as false positives.

4.1 What counts as an anomaly?

We treat an event as anomalous if it deviates from expected patterns in any of these ways:

A) Identity/context anomalies

-

unexpected processes performing certain event types

-

unusual activity concentrated on a particular host

-

unusual user contexts (

userId) for a given process

B) Action anomalies

Even common events can be suspicious depending on context. For example, the top suspicious event types in validation include:

-

openat(198),lstat(195),close(149) -

stat,fstat, directory listing (getdents64) -

plus destructive operations such as

unlink/security_inode_unlink

So “anomalous” here is not “rare eventName”—it’s unusual combinations of (process, host, event type, args) and the surrounding context.

C) Argument anomalies (args)

The args field is semantically rich. It can contain:

-

high-signal tokens (e.g.,

PR_SET_NAME) -

flags/options and numeric argument structure

-

patterns that can distinguish benign from suspicious actions

A safety layer that ignores args will often miss the strongest indicators of unusual behavior.

D) Outcome anomalies (returnValue)

Non-zero return codes (or unusual return patterns) can indicate failed access attempts, probing, or misconfiguration. In isolation, errors aren’t malicious—but in combination with other signals, they can raise risk.

4.2 Attacker and operational assumptions

This dataset reflects two realistic constraints common in cybersecurity:

-

Incomplete attack labels

Training/validation do not includeevil=1, so we cannot rely on supervised malicious labels. -

Distribution shift / incident conditions

What “normal” looks like can change rapidly. A threshold tuned for rare anomalies during normal operations can fail when the environment becomes attack-heavy. Resilience requires adapting the alerting policy (e.g., by increasing alert budget or switching to incident-mode behavior).

4.3 Why this is a “safety layer” for agentic systems

The exact same threat model applies to agentic AI—especially in retail investing—if we map:

-

processName/userId↔ agent identity + user account -

eventName↔ tool/function invoked (place order, cancel, fetch news, rebalance) -

args↔ tool arguments / payload (ticker, quantity, price limits, endpoint responses) -

returnValue↔ tool response / error codes

In both cases, the safety layer must:

-

detect abnormal action-argument combinations

-

handle label scarcity

-

remain robust under base-rate shift

-

and support trust via manageable alert volume and interpretable triage

# Top event and process types (train)

display(dfs["train"]["eventName"].value_counts().head(10))

display(dfs["train"]["processName"].value_counts().head(10))

# Suspicious events distribution (validation)

val_sus = dfs["val"][dfs["val"]["sus"]==1]

display(val_sus["processName"].value_counts().head(10))

display(val_sus["eventName"].value_counts().head(10))

Feature engineering: baseline vs args-aware features (final)

This segment is where we explain why the model behaves differently in “trust mode” vs “incident mode.” The short version: the args field contains the richest signal, but leveraging it can change the alerting behavior depending on how you calibrate thresholds.

5.1 Design goal: features that support a safety layer

For a safety layer, we care about two things:

-

Operational reliability: fast, stable features that work at scale

-

Semantic signal: features that capture what the event actually did (often in

args)

We therefore build two feature sets:

-

Baseline (lightweight): stable, cheap features suitable for trust-mode calibration

-

Args-aware (enhanced): adds structure extracted from

argsto better detect high-severity behavior during incidents

5.2 Baseline features (lightweight, trust-mode friendly)

Baseline features are mostly numeric/contextual:

-

timestamp -

processId,threadId,parentProcessId,userId,mountNamespace -

eventId,argsNum,returnValue -

simple proxies:

-

args_len(length ofargsstring) -

stack_len(approx. length ofstackAddresseslist)

-

Why this helps: It provides a stable signal without overfitting to rare argument patterns. In practice, this can produce a detector that’s easier to calibrate for low false positives during normal operations.

5.3 Args-aware features (enhanced, incident-mode strength)

The enhanced feature set extracts structured signals from args:

-

args_count: number of arguments -

args_unique_names,args_unique_types: diversity measures -

counts by type/value structure:

-

args_int_cnt,args_ulong_cnt,args_str_cnt,args_num_cnt

-

-

robust numeric summaries (after fixing NaN/Inf issues)

-

high-signal flags:

-

args_has_pathlike,args_has_ip,args_has_url -

token presence like

args_has_pr_set_name

-

Why this helps: During attack-heavy conditions, malicious events often differ strongly in argument structure and tokens (e.g., unusual flags, parameters, payload-like strings). These features can sharply increase detection power for severe behavior (including evil)—at the cost of potentially increasing noise in normal operations if not carefully calibrated.

This is the exact feature construction approach used in our experiments.

Code: training + evaluation (trust mode + incident mode)

This block is blog-ready and mirrors the workflow used in our experiments.

(You can run it for baseline_cols or enhanced_cols.)

import numpy as np

from sklearn.ensemble import IsolationForest

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report, average_precision_score, roc_auc_score, precision_recall_fscore_support

def fit_iforest_and_score(feature_cols):

train = dfs["train"]

val = dfs["val"]

test = dfs["test"]

# train on normals only

X_train_norm = train.loc[train["sus"]==0, feature_cols].replace([np.inf,-np.inf], np.nan).fillna(0.0)

X_val = val[feature_cols].replace([np.inf,-np.inf], np.nan).fillna(0.0)

X_test = test[feature_cols].replace([np.inf,-np.inf], np.nan).fillna(0.0)

model = IsolationForest(n_estimators=300, random_state=42, n_jobs=-1)

model.fit(X_train_norm)

val_score = -model.score_samples(X_val)

test_score = -model.score_samples(X_test)

return model, val_score, test_score

def eval_ranking(scores, y, name):

print(f"\n=== {name} (ranking) ===")

print("PR-AUC:", average_precision_score(y, scores))

print("ROC-AUC:", roc_auc_score(y, scores))

def eval_threshold(scores, y, thr, name):

pred = (scores >= thr).astype(int)

print(f"\n=== {name} (thresholded) ===")

print(classification_report(y, pred, digits=4, zero_division=0))

def trust_mode_threshold(val_score, y_val, fpr_target=0.01):

# threshold from normal validation scores

thr = np.quantile(val_score[y_val==0], 1 - fpr_target)

return float(thr)

def eval_alert_rate(scores, y, alert_rate, name):

thr = np.quantile(scores, 1 - alert_rate)

pred = (scores >= thr).astype(int)

p, r, f1, _ = precision_recall_fscore_support(y, pred, average="binary", zero_division=0)

print(f"{name} alert_rate={alert_rate:.3f} thr={thr:.4f} precision={p:.3f} recall={r:.3f} f1={f1:.3f} flagged={pred.mean():.3f}")

# Example usage:

# model, val_score, test_score = fit_iforest_and_score(baseline_cols) # or enhanced_cols

# y labels

y_val_sus = dfs["val"]["sus"].values.astype(int)

y_test_sus = dfs["test"]["sus"].values.astype(int)

y_test_evil = dfs["test"]["evil"].values.astype(int)

# Ranking quality

# eval_ranking(val_score, y_val_sus, "VAL sus")

# eval_ranking(test_score, y_test_sus, "TEST sus")

# eval_ranking(test_score, y_test_evil, "TEST evil (severity check)")

# Trust-mode thresholding

# thr = trust_mode_threshold(val_score, y_val_sus, fpr_target=0.01)

# eval_threshold(val_score, y_val_sus, thr, "VAL sus (trust mode)")

# eval_threshold(test_score, y_test_sus, thr, "TEST sus (trust mode)")

# Incident-mode alert-rate policy

# for ar in [0.01, 0.05, 0.10, 0.20]:

# eval_alert_rate(test_score, y_test_sus, ar, "TEST sus (incident mode)")7 — Results (baseline for trust mode, enhanced for incident mode)

7.1 Trust mode (validation, rare anomalies)

In validation, suspicious events are rare, so we calibrate conservatively to avoid alert fatigue. Using the baseline feature set with Isolation Forest trained on normal-only events, we set the threshold to cap false positives on normal validation events (≈1% FPR on validation normals).

Validation performance (sus):

-

PR-AUC: 0.181

-

ROC-AUC: 0.990

-

At the trust-mode threshold:

-

Precision: 0.194

-

Recall: 0.634

-

F1: 0.297

-

Interpretation: the anomaly score separates suspicious from normal events extremely well (ROC-AUC ≈ 0.99). Under an operationally conservative threshold, the detector catches a majority of suspicious events while keeping alerts manageable.

Practical takeaway: in normal operations, the limiting factor is not model separability—it’s trust calibration (keeping false positives low enough that alerts remain actionable).

7.2 Incident mode (test, attack-heavy distribution shift)

The test split behaves like an incident: suspicious events are the majority, and evil=1 appears heavily. Under this shift, a fixed trust-mode threshold becomes too strict (recall collapses). Instead, we use the enhanced args-aware feature set and evaluate under an incident policy.

First, the anomaly score itself remains highly informative:

Test ranking quality (incident regime):

-

susPR-AUC: 0.990 -

susROC-AUC: 0.938 -

evilPR-AUC: 0.989 -

evilROC-AUC: 0.970

Interpretation: even though evil does not appear in training/validation, the model’s anomaly score still ranks high-severity malicious events above normal activity. That’s exactly the behavior you want from a safety layer trained under incomplete labels.

Practical takeaway: during incidents, the score is useful—but the alerting policy must adapt.

7.3 Incident policy: adaptive alert rate (resilience knob)

Instead of a fixed threshold, incident response uses an alert-rate policy: flag the top X% most anomalous events. This is operationally realistic because it maps directly to monitoring capacity and risk level.

Using the enhanced model on the test split:

-

Alert ~5% (flagged ~7.4% due to score ties):

precision 0.985, recall 0.081, F1 0.149 -

Alert ~10% (flagged ~11.8%):

precision 0.990, recall 0.129, F1 0.229 -

Alert ~20% (flagged ~30.3%):

precision 0.996, recall 0.333, F1 0.499

This gives a clean resilience control:

-

when risk is low → keep alert rate low (trust)

-

when risk is high → increase alert rate to regain recall (resilience)

7.4 Triage quality: top-K alerts

Another incident-friendly policy is top-K triage: review the highest scoring K events first. This is useful when a human responder needs immediate focus.

Using the enhanced model on test:

-

Top-100 alerts: precision 0.93

-

Top-500 alerts: precision 0.91

Recall is low at small K (because the incident contains many anomalous events), but top-K precision demonstrates that the model can produce a high-quality ranked triage list under pressure.

7.5 Summary: what we learn from the results

-

Trust mode works best when calibrated on rare-anomaly validation data (baseline features + conservative threshold).

-

Incident mode requires policy adaptation (alert rate / triage), because base rates shift dramatically.

-

Args-aware features improve detection of severe behavior and generalize well to

evileven without seeingevilin training.